Hogar Alegría (Happiness Home) is a home for the aged, sponsored by the Catholic Church in Neiba, a town in the southwest part of the Dominican Republic. Dedicated in May, 1979, it stands as a testimony to Christ’s command to love your neighbor and aid the poor.

Hogar Alegría is not a nursing home; there is no capacity for long-term bed care. Instead, within it, a functioning society is being formed for those rejected by the world; men and women too old or sick to perform the heavy manual labor required to survive in a developing country, without means of support. Christian ideals and helping one another, are the basis for the society.

Those who can walk push the wheelchairs of the disabled, the sighted lead the blind. In this community, people offer the things they have and receive the things they need.

A full range of services are provided for the residents. Clothing to replace rags, transportation and connections to the public hospital for medical care, simple nourishing food, and activities. In a typical day, the morning is spent performing simple chores, aiding the small staff. Men might cut grass while women sweep or wash. Afternoons are for community activities such as games, discussions and singing. Every other Sunday is fiesta day, with local groups providing entertainment in the afternoon. Disproving their age, the fiestas always end with merengue dancing by all.

At present, there is capacity for 100 residents, all beds now being filled. Hogar Alegría is the only institution of its kind in the southwest region to fill the vast needs of the aged poor. In time, Hogar Alegría will hopefully become a center for aiding other handicaps in the population: deaf-mutes, the blind, disabled, leading the way that the state will see and fulfill its obligations to society.

Currently, Hogar is being managed by Sor Lourdes of “Hermanas de Nuestra Señora de Perpetuo Socorro.” The Sisters are also trained nurses.

In February of 2012, while on a business trip to the Dominican Republic, I returned to Neiba to check on the status of Hogar. I found the original facility, still offering services to the aging poor, but with a physical structure in obvious need of repair. Many structural problems were plain to see, including leaking and deteriorating ceilings/roofs, plumbing and electrical shortages, wall cracks, peeling paint, etc. Also, additional staff (care givers) and improved nutritional programs were obviously in need. With more staff and programs, Hogar would be able to provide more services, and care for more residents.

I established Hogar Alegría-PDX as a non-profit entity to aid in the support of Hogar Alegría, Dominican Republic.

My plan is to assist Hogar through Hogar-PDX in funding the above-mentioned projects so that it may run again as it did at its inception. The need is great and the resources have been limited. The Bishop of Barahona, along with the Sisters currently working there, and the residents are all supportive of this effort and want to do all they can to improve Hogar and the lives of those who depend on it.

Sincerely,

Steve Amdahl

Following are stories of 5 residents of Hogar Alegría

Angelito

Angelito has the distinction of being the first resident of Hogar Alegría. After all the work and preparations, finally there would be a beneficiary. But what a shock! Instead of a more or less vigorous old man, Angelito was carried in more dead than alive.

Angelito led a luckless life. Born to a small farmer in the hills, he knows neither birthday or age. By his own admission he seldom played as a child, rarely went to town. As a young man he farmed his plot of land and hired out to work.

Things would have continued as such, but an accident broke his back. Without medical care, it healed badly, leaving him crippled. His wife and child left him and Angelito was left to spend his life crawling on hands and knees.

For 20 years he lived by crawling from his hole in the ground to neighbors, looking for scraps of food. A local school teacher brought his name to the board of Hogar Alegría, then being finished. He was accepted and brought as soon as the builder’s dust was cleaned from a bedroom.

Angelito needed an immediate blood transfusion. A day’s telephoning and driving found enough donors for a complete blood change.

Angelito’s second large problem, malnutrition, was easily solved by three square meals daily. Cleaned up, with new clothes, the change was incredible. Color and vigor returned, his head came up off of his chest. Until today, he mows the lawn of Hogar Alegría, locking his wheelchair and cutting around himself with an old push lawnmower, then moving on. Angelito is a functioning, contributing member of the society of Hogar Alegría.

Hepa

Hogar Alegría has become a refuge for all types of people. Hepa, an alcoholic, is one of our later arrivals. An erect, coal black man with white clipped hair, his 60 plus years were spent working as a field hand and drinking his money away. Before he arrived we were warned that “Happiness Home” wouldn’t be very happy if Hepa came in drunk.

Helping an alcoholic regain control over his life again is a difficult task. Regular meals solved Hepa’s health problems and being away from daily contact with his former environment lessened drinking temptations for him. An active mean, Hepa can’t sit still. One finds corn planted among the flowers, pigeon peas growing in the lawn, squash along the road, all a result of his nervous activities. Hepa has been given the task of watching over the parochial school’s playground, an ideal job. For people like Hepa, Hogar Alegría means a life of dignity they never knew before.

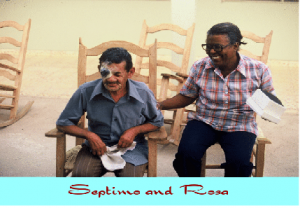

Septimo

Septimo Perez is perhaps the most unusual resident of Hogar Alegría. Unusual in the sense of having a dead man on his head. Don’t you see him there, sprawled over Septimo’s head, with legs draping down the sides of Septimo’s baggy green shirt?

Septimo Perez is perhaps the most unusual resident of Hogar Alegría. Unusual in the sense of having a dead man on his head. Don’t you see him there, sprawled over Septimo’s head, with legs draping down the sides of Septimo’s baggy green shirt?

Septimo, or Bejucco as he is called, was a sad case when he arrived. Nearly blind, filthy with lice from his hovel, hungry and skinny, he spent all of his waking hours picking and tugging at his hair, the hundreds of wrinkles and crags on his ruined face, the hair on his chest. He bumped around with a dirty white handkerchief covering his head.

One night, Bejucco told his tale of woe. He had a small farm on an acre or two of land. Being old and almost blind, he rented it out. When the harvest came, Bejucco tried to collect his rent. But the tenant wouldn’t pay, and brought a witch doctor who threw a dead man over Bejucco’s head. With a dead man on his head, he had little time to worry about other things. So that was it! With thumb and forefinger he spent his days tugging out strands of dead man.

Pausing to pick out a piece of dead man, he continued. What he really needed now, he explained, was to go back to his town, find his own witch doctor and have the dead man washed away. After two months at Hogar Alegría he felt strong enough to go. Could we help?

Two weeks later, again seated in front of us, tugging at his back and wiping his forehead with a dirty rag, he recounted his treatment. Seven baths with seven roots were needed; he had taken four with three more to go. Sitting here getting a pot belly from rice and beans, he even cracked jokes about brujos as he pulls a stringy piece of dead man from his hair.

Euvirgen

“ I am called Euvirgen Altagracia! Praise the Lord and the Virgin Altagracia!”

I am called Euvirgen Altagracia! Praise the Lord and the Virgin Altagracia!”

Who was this hurricane bearing down on me, arms raised to heaven, enormous smile gaping with missing teeth, gray eyes twinkling in a swarthy grandmotherly face?

“I’m named after the Virgin, Padre, Euvirgin Altagracia! Praise the saints!”

“That’s great, but I’m no padre.”

“Praise the Lord and the Virgin! I’m Euvirgin Altagracia after the Virgin. Say, Padre, could you bring me a statue of the Virgin?”

“But I’m no padre.”

“Praise the Virgin with the Lord in front!” A huge embrace and she roared off in search of clothes to be washed or dirt to be swept.

Euvirgin was a poor lady living alone and not making ends meet. Hearing about Hogar Alegría as a refuge for the elderly, she set out on foot to Neiba, a day’s walk from her village. Euvirgin is a hard worker and her trademark, upraised arms supplicating heaven, has become a fixture. But Euvirgin still had some surprises.

“Padre, Padre, look who came! Jose Altagracia! St. Jose and the Virgin be praised!”

Standing in ruined splendor was Jose Altagracia. Greasy brown hat, dark eyes glaring from belittling brows, enormous nose, three days growth of stubble peppering his black face. His rags fluttered in the wind as he leaned on his walking stick, left big toe sticking out at a 45 degree angle from his foot. Jose and Euvirgin Altagracia.

Jose had not been living with his wife, Euvirgin. She left town without telling him, and after a week he set out to find her. There ensued a fight of truly Olympic proportions, Jose ordering his recacitrant wife, Euvirgin, home. But it ended amicably enough: Jose seated in the dirt, slouching against a wall, Euvirgin squatting beside him, discussing intricate blood lines of distant relatives. Jose was here to stay.

“Say, Padre, about the statue?”

“I’m no padre.”

“I know but you should be!” Toothy smile and big hug.

Envirgin and Jose Altagracia, two poor people finding refuge at Hogar Alegría.

Damariz

Damariz, a deaf-mute, is not a resident of Hogar Alegría but has been helped through her association with it. A cute, pigtailed girl of 12, she is the daughter of a cook at Hogar Alegría.

Eyes alive and sparkling, she is an exceptionally intelligent child, sewing clothes and loving to play all sorts of games. Damariz has been adopted into the community of Hogar Alegría. Her association with Hogar Alegría has permitted her to attend the parochial school in Neiba, and later this fall she will attend a deaf-mute school.